Consensus decision-making: go with the flow

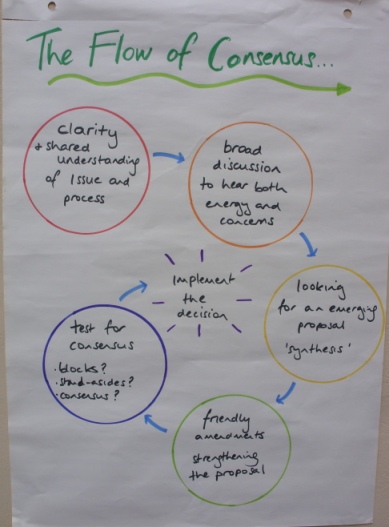

In our previous posts we’ve talked about what consensus is and is not and why groups might choose to use it. But we haven’t (yet) got down to the detail about how it works. So to remedy that this post aims to lay out the flow of an effective consensus decision and highlight key moments in that process which, if not handled with care, can pour sand in the smooth running of a consensus decision. This post will give you an overview. We’ll follow it with posts on each stage of the flow in detail – common problems that arise, and what a group and facilitator can do to deal with them successfully.

There are quite a few models of consensus out there. Some, I feel, give too little information (have a discussion…make a proposal….). Others, perhaps, go the other way and tell you what techniques to use at what stage of the process (have an ideastorm…then have a go-round). As a facilitator I don’t find this helpful. I want to use the right technique for the specific group I’m working with and for the specific issue under discussion. In many cases this may be an ideastorm followed by a go-round but those things themselves are not the flow of consensus. So what I hope is presented here is a middle path – detailed enough to flag up important issues, but not prescriptive. So to the flow…

Step 1: Be clear and ensure your clarity is shared: These first few minutes can be crucial for framing what happens in the rest of the discussion. If the group aren’t clear on the decision to be made or the process to be used you can waste a lot of time and cause unnecessary confusion, even conflict. Common examples of problems caused by lack of clarity include:

Step 1: Be clear and ensure your clarity is shared: These first few minutes can be crucial for framing what happens in the rest of the discussion. If the group aren’t clear on the decision to be made or the process to be used you can waste a lot of time and cause unnecessary confusion, even conflict. Common examples of problems caused by lack of clarity include:

- discussing issues you simply don’t have enough information to decide upon

- talking at cross purposes and then having to take time to untangle the mess

- excluding newcomers who haven’t been inducted into the groups process and aren’t familiar with the agenda

All this, and more, can be avoided simply by checking in with the group and having a short discussion on what the group think the agenda item is about. Many people would say that it’s obvious what we’re talking about, but, as I’ve been heard to utter on many occasions, “my obvious is often different from your obvious”.

Step 2: Have a broad and inclusive discussion – inclusive of both a wide range of people and ideas. The aim of the game here is to ensure that the discussion is wide enough for people to build a real sense of ownership around the issue; to explore a variety of ideas; and, vitally, to hear people’s concerns. Bottom line in consensus – if concerns aren’t dealt with adequately, a group cannot reach consensus. This can feel like precious time the group doesn’t have, but it ensures a stronger outcome with a higher level of group commitment, leading to far better implementation. Time well spent.

Step 2: Have a broad and inclusive discussion – inclusive of both a wide range of people and ideas. The aim of the game here is to ensure that the discussion is wide enough for people to build a real sense of ownership around the issue; to explore a variety of ideas; and, vitally, to hear people’s concerns. Bottom line in consensus – if concerns aren’t dealt with adequately, a group cannot reach consensus. This can feel like precious time the group doesn’t have, but it ensures a stronger outcome with a higher level of group commitment, leading to far better implementation. Time well spent.

Step 3: Pull together, or synthesise, a proposal that emerges from the best of all the group’s ideas, whilst simultaneously acknowledging concerns. That’s a pretty tall order and a group won’t always get it right at the first go. Unless your listening skills are fantastic, and the group has made all of its concerns conscious, there may be some time spent moving back and forth into discussion until the final pieces come together to give you an appropriate proposal. The key thing here is that the proposal is inclusive – it doesn’t marginalise anyone.

Step 3: Pull together, or synthesise, a proposal that emerges from the best of all the group’s ideas, whilst simultaneously acknowledging concerns. That’s a pretty tall order and a group won’t always get it right at the first go. Unless your listening skills are fantastic, and the group has made all of its concerns conscious, there may be some time spent moving back and forth into discussion until the final pieces come together to give you an appropriate proposal. The key thing here is that the proposal is inclusive – it doesn’t marginalise anyone.

Step 4: Friendly amendments – tweak the proposal to make it even stronger. You’re looking for the best possible proposal that you can formulate with the people, time, and information that you’ve got. Are there any niggling doubts that can be addressed by a change of language or a tweak to the idea? After a little reflection (cue: cup of tea) are there any ways in which the proposal can be improved upon? These are known as friendly amendments. What they are not is an attempt to water down a proposal so far that it becomes meaningless – death by a thousand amendments. Nothing friendly in that thinking (nothing consensual either!).

Step 4: Friendly amendments – tweak the proposal to make it even stronger. You’re looking for the best possible proposal that you can formulate with the people, time, and information that you’ve got. Are there any niggling doubts that can be addressed by a change of language or a tweak to the idea? After a little reflection (cue: cup of tea) are there any ways in which the proposal can be improved upon? These are known as friendly amendments. What they are not is an attempt to water down a proposal so far that it becomes meaningless – death by a thousand amendments. Nothing friendly in that thinking (nothing consensual either!).

Step 5: Test for consensus – do we have good quality agreement? So far the flow we’ve presented could be for any decision-making system looking to maximise participation. It’s at Step 5 that it becomes uniquely consensus. That’s because this is where we entertain the possibility of agreeing to disagree and of the veto (or block, major objection or principled objection – it goes by a lot of names). So let’s reflect a minute. We’ve got a shared agreement on the issue we’re discussing. We’ve given it the time it needs to explore diverse perspectives, to hear of concerns and possible concerns and out of that we’ve drawn together a proposal that seems to have the energy of the group behind it. We’ve paused and then tried to make the proposal even stronger, taking into account some concerns we hadn’t heard clearly enough before. We’ve restated the proposal so we’re all clear what we’re being asked to agree to (or not). Now the facilitator asks us 3 questions:

Step 5: Test for consensus – do we have good quality agreement? So far the flow we’ve presented could be for any decision-making system looking to maximise participation. It’s at Step 5 that it becomes uniquely consensus. That’s because this is where we entertain the possibility of agreeing to disagree and of the veto (or block, major objection or principled objection – it goes by a lot of names). So let’s reflect a minute. We’ve got a shared agreement on the issue we’re discussing. We’ve given it the time it needs to explore diverse perspectives, to hear of concerns and possible concerns and out of that we’ve drawn together a proposal that seems to have the energy of the group behind it. We’ve paused and then tried to make the proposal even stronger, taking into account some concerns we hadn’t heard clearly enough before. We’ve restated the proposal so we’re all clear what we’re being asked to agree to (or not). Now the facilitator asks us 3 questions:

- Any blocks? Does anyone feel that this proposal runs contrary to the shared vision of the group and as such will damage the integrity of the group, potentially even causing people to leave? If you’ve done the work well to this point, the answer will usually be “no”. But let’s not assume…. give people time, and if there are no blocks move on to the next question. However if there are blocks you need to back up – is it enough to continue to amend the proposal or do you need to return to the broad discussion (which obviously wasn’t broad enough first time round….)?

- Any stand-asides? Does anyone disagree with the proposal enough, on a personal level, that they don’t want to take part in implementing it (but is happy for the rest of the group to go ahead, without feeling in any way a lesser part of the group for it)? It’s worth checking here that there aren’t too many stand-asides as that’s an obvious sign of a lukewarm response to a proposal. And we can do better than lukewarm.

- Do we have consensus? Assuming there are no blocks, and no more than a manageable number of stand-asides, can we assume that we agree? No – never assume, so ask the question and insist on a response. Lack of response may indicate ‘consensus by lack of will to live’…. the “I’ll agree to anything just as long as this interminable meeting ends” syndrome.

And this is where a lot of groups finish and pile down the pub to celebrate another well made decision. But what about Step 6?

Step 6: Make it happen. Making the decision is just the start of a longer process, and unless there are definite steps taken to ensure that people sign up to specific tasks, with specific deadlines and so on, decisions are meaningless. So who’s going to do what, by when? For some decisions it may be as simple as typing up the agreed form of words and filing it, but that’s still an action and still needs someone to make it happen. For other decisions it may need complex timelines and multiple volunteers or staff members to engage in taking the decision forward.

Step 6: Make it happen. Making the decision is just the start of a longer process, and unless there are definite steps taken to ensure that people sign up to specific tasks, with specific deadlines and so on, decisions are meaningless. So who’s going to do what, by when? For some decisions it may be as simple as typing up the agreed form of words and filing it, but that’s still an action and still needs someone to make it happen. For other decisions it may need complex timelines and multiple volunteers or staff members to engage in taking the decision forward.

But if your consensus process is working well, this won’t be the drag it often is at the end of fractious meetings when people are tired and grumpy. In theory the group has just made a high quality decision that it has energy for – so ride that wave of enthusiasm and get folk signed up!

That’s that decision made – now onto the next agenda item….

Other posts in this series:

- Consensus decision-making: what it is and what it is not

- Consensus decision-making: Why?

- A brief history of consensus decision-making

More detail on the steps of the consensus process:

- Consensus decision-making: the first step

- Consensus decision-making: the muddle in the middle

- Consensus decision-making: weaving it all together

- Consensus decision-making: the moment of truth

Consensus decision-making: the first step | rhizome: participation|activism|consensus

April 7, 2011 @ 5:02 pm

[…] rhizome: participation|activism|consensus Skip to content HomeBlogAbout RhizomeContact RhizomeThoughts on Rhizome’s organisation and structureValues, ethics and practiceWho we are (at the moment)What we doCapacity BuildingEducationFacilitationSharing informationTrainingWhat you sayLinksResources ← Consensus decision-making: go with the flow […]

Consensus decision-making: what it is and what it is not | rhizome: participation|activism|consensus

April 7, 2011 @ 5:04 pm

[…] Pingback: Consensus decision-making: go with the flow | rhizome: participation|activism|consensus […]

Consensus decision-making: Why? | rhizome: participation|activism|consensus

April 7, 2011 @ 5:06 pm

[…] rhizome: participation|activism|consensus Skip to content HomeBlogAbout RhizomeContact RhizomeThoughts on Rhizome’s organisation and structureValues, ethics and practiceWho we are (at the moment)What we doCapacity BuildingEducationFacilitationSharing informationTrainingWhat you sayLinksResources ← To sum it up… Consensus decision-making: go with the flow → […]

Consensus decision-making: the muddle in the middle | rhizome: participation|activism|consensus

April 20, 2011 @ 8:33 pm

[…] you remember back to our consensus flowchart the middle stages involve a broad exploratory discussion out of which we try to draw a proposal, a […]

Consensus decision-making: the moment of truth | rhizome: participation|activism|consensus

May 3, 2011 @ 2:04 pm

[…] covered the mechanics of this step of the process in previous post, as well as an introduction to the veto, or block, so I’ll paste what’s already been […]