How not to take decisions: voting, chess and alcohol!

A while back, I attended the AGM of my local chess club, held in the room where we play, upstairs in a pub. We ploughed through the agenda in a manner that was low-key and low energy – until the very last item.

A while back, I attended the AGM of my local chess club, held in the room where we play, upstairs in a pub. We ploughed through the agenda in a manner that was low-key and low energy – until the very last item.

The fuse was lit by Richard, a teacher who runs his school’s chess club. Occasionally, he brings some of his chessplayers – some as young as 10 or 11 – along to the club, to experience playing against adults. Even more occasionally, parents express qualms about the venue being a pub. He felt that these qualms would be allayed if he could say that no-one playing or coaching a student would be consuming alcohol. Could we make a policy to this effect?

The discussion went off in all directions. it was ludicrous to stop those playing or coaching a student from drinking alcohol while adjacent players were busy with their beer. What about people who had a drink or four before the game? Surely the alcohol would still be in their bloodstream and affect their behaviour? Wasn’t this, underneath, a moralistic crusade against alcohol? Rather than banning alcohol, shouldn’t we ban the kids? A policy like this would be inconsistent with our policy on smoking. And so on.

All good knockabout stuff, but I wanted to finish the AGM and play some chess, so I made a proposal on the lines suggested by Richard. The chairman (I’ll use the term that was used in the meeting) put it to the vote, it squeaked through by 4 votes to 3, and the chairman could declare the meeting closed.

Making decisions in this form must be familiar to many of us, and so familiar that it feels natural. That makes it doubly worthwhile to tease out its flaws.

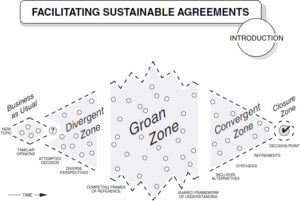

It’s almost always right to start by opening up the discussion, as happened here, to bring out a a range of attitudes, points of information and ideas. That done, though, there should be gradual convergence to a decision, rather than the abrupt conclusion that took place here.

It’s almost always right to start by opening up the discussion, as happened here, to bring out a a range of attitudes, points of information and ideas. That done, though, there should be gradual convergence to a decision, rather than the abrupt conclusion that took place here.

Why so? Look at what we never found out. We never established what people really valued. My priority was to keep Richard happy and ensure that his juniors kept on visiting the club. Herefordshire, where I live, used to have a dozen clubs. Now there is just one, with a membership in decline. If it and others are to survive, it seems to me critical that young players get used to playing in clubs like ours, as opposed to online and alone. But we never found out if this view was shared by others, nor what other values and principles were held dear.

Furthermore, my proposal was the only one we considered. One or two alternatives came up in the discussion, such as putting all the juniors together, in a little ghetto down one end of the room. But there was no attempt to identify a full range of possibilities. Were there other ways for Richard to keep parents happy? Could we find a venue other than a pub? Even if ultimately rejected, elements of such ideas might have enriched the final choice – just as a decent chess-player may choose a plan based on ideas from different lines of play.

The second flaw lay in the use of voting. There was one vote, it was decisive, and it concluded discussion of the item. This will feel natural to those used to debates. Yet it could have been so different. I mean no criticism of our chairman in what I am about to say – he simply did what most would have done in the circumstances. There were several points at which he could have taken a show of hands, to check which attitudes were shared and which were one person grandstanding.

Also, the vote did not need to be the final act. The chairman could have deplored the narrow majority and asked for extra proposals that might prove more popular. These could have been variations on mine, or quite different. A show of hands would test the water. The most popular could then have been put to a formal vote.

The tools that we have for taking decisions are simple: talking and voting. But the ways in which we use and combine them are many and varied.