Taking decisions – defining consensus

Continuing our series of posts about decision-making, here we explore the definition of consensus. Let us know about your experiences of consensus in practice or in the comments below.

Continuing our series of posts about decision-making, here we explore the definition of consensus. Let us know about your experiences of consensus in practice or in the comments below.

There are resources available to help you in your decision‑making, on facilitation, on consensus decision‑making, and a plethora of our older resources here for even more tips and tricks.

If you’re a bit stuck, are facing a particularly difficult decision, or would just like an external facilitator to support your decision‑making and group‑work, get in touch.

Read more about our facilitation services, and other help we can give you.

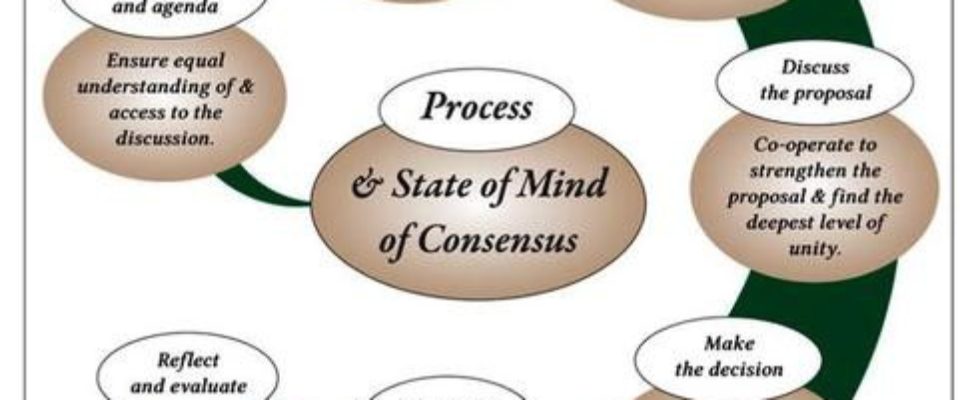

Consensus is often defined very loosely. The ‘Consensus Handbook’ produced by Seeds of Change simply says that “a consensus group is committed to finding solutions that everyone can actively support, or at least can live with”.

I’d like to be more precise, and say that consensus decision-making has two features. First, everyone involved states their view explicitly. ‘Explicit’ is important, Conscious Consumers in Canterbury in Kent, was one of twelve groups in six European countries whose decision-making was studied in a research project. Taking all twelve together, just over half the decisions were described as being ‘nodded through’. That’s not being explicit.

Second, everyone agrees to a decision; or, at least, doesn’t disagree. In consensus decision-making, people may express disagreement in two forms. They may ‘stand aside’ because, while they may not like the decision, they support it for the good of the group. Or, they may block the decision. In that case, there is no consensus, and the discussion continues.

Second, everyone agrees to a decision; or, at least, doesn’t disagree. In consensus decision-making, people may express disagreement in two forms. They may ‘stand aside’ because, while they may not like the decision, they support it for the good of the group. Or, they may block the decision. In that case, there is no consensus, and the discussion continues.

Third, the decision is taken, as Wikipedia puts it, “in the best interest of the whole”. When discussion gets heated in meetings of a housing coop called Threshold in Dorset, this is the question they pose: “Is this issue more important to you than the group?”

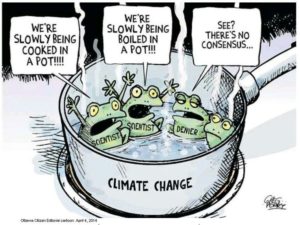

Groups differ in whether a blocker needs to give reasons for doing so and, if so, the nature of those reasons. For example, in sociocracy, a near-consensus method, people do have to give reasons for their objections, and they have to be ‘reasoned and paramount’. ‘Paramount’ means that someone’s objection relates to the fundamental purpose of the group.

When defining consensus I referred to ‘everyone involved’. That needs a bit of unpicking. Every group needs to decide what they mean. For instance, does every member of the group need to agree for a proposal to go through, or only those who have turned up to the meeting? Sociocracy seeks the agreement not of everyone but of those affected.

I very much like the natural way in which this happens in the South Seas, according to an American diplomat called Harland Cleveland:

“In a Pacific island village, important decisions will draw all the villagers to a community circle, but only those who care about a particular decision will edge toward the circle’s centre to make their views known and their weight felt. The others will sit around the outside, often talking among themselves about something else. When the village elder is able to divine and announce the common view, that doesn’t mean that everybody is an uncritical endorser of what will be done. It does mean that among those whose water-buffaloes might be gored [the topic under discussion], there is at least passive acquiescence, and those who don’t much care are willing to leave the outcome to those who do.”

March 24, 2018 @ 10:13 am

Working with Perry (author of this post) over the past several years has been enlightening. I’ve never met anyone so willing to trust in the intelligence and wisdom of others to take decisions their absence. It’s a very refreshing change from the all too prevalent attitude of “If I wasn’t fully included then I need to be suspicious of the decision that was taken”.

Sure, not every group is great at considering the needs and interests of those who could be affected by the decision, but aren’t present when it’s made. However I’d say that an (the?) essential part of the consensus process is developing this very skill – empathy, reflection, consideration of other’s needs and as Perry says taking a decision “in the best interest of the whole”.

Without developing this mindset we seem to default to an attitude that slowly kills consensus and leaves a meaningless husk of a process behind. That attitude says that we all have to be involved in all stages of every decision, that we can’t trust a decision otherwise, that essentially unless we get our way the decision is a poor one.

Ultimately it’s a very individualistic attitude – it sees decisions being made by individuals coming together in a loose and fragile coalition rather than by a coherent group in which people genuinely understand that together they are wiser and stronger than they are apart. These ‘groups’ work so long as everything is running smoothly but fracture all too quickly when differences emerge.

In this world the only sound decision is an enthusiastically unanimous one made by the full group. Ever tried reaching a decision like that in human rather than geological time?

So consensus requires this understanding that it is unity but not unanimity; that we can trust others to make sound decisions in our absence; that with enough work on the part of the group it is possible to have our voices heard even when we’re not in the room, or are in the room but hold back from speaking; that sound decisions are not necessarily the decision we would have made; and that we all benefit from being part of groups, communities and organisations

Rhizome newsletter early summer 2018 - Rhizome

August 16, 2018 @ 11:39 pm

[…] a whirlwind history of consensus, and join us discussing whether it needs everyone to […]